Recently, I’ve been pondering “sympathy,” and “pity. Specifically, I’ve been pondering these words in terms of their ability to motivate people to help other people.

And here’s the realization I’ve drawn: Sympathy and pity are overrated, and I don’t believe that they’re a requisite to do good in the world.

This confession may sound bizarre, coming from someone who’s worked in public service since 18, so let me explain.

Six years ago, when I lived in Washington State, I got into meditation. I’d just returned from Afghanistan, and my life was in a state of flux.

During my 15-month deployment (and in the three months that followed), I’d experienced a string of losses. Among them: three soldiers in my unit killed by a suicide bomber, the end of a two-year romantic relationship, and a fall-out with a female friend. Additionally, everyone at home had changed. Or maybe I’d changed. All I know is that I couldn’t relate to anyone, and no one (except other soldiers) could relate to me.

Those were shitty days. A doctor prescribed antidepressants, but I have a fear of drugs so I didn’t take them. Sitting in the lotus position on a mat while I pondered each inhalation and exhalation as though it was a poem — at home or in a Buddhist meditation center — was the only thing that could calm my mind.

I’m fairly certain it saved me.

Once, at a three-day meditation retreat, I told another meditator that certain people — the poor, the mentally ill, the physically disabled — invariably invoked feelings of sympathy and pity within me. “I always feel so bad for them,” I explained.

I was surprised by the woman’s response. To paraphrase: “Did you ever consider that feelings of sympathy and pity create a separation between you and the other person?” she said. “When you choose to feel sympathy and pity toward a person, you’re basically signaling that you or your circumstances are superior to that person or that person’s circumstances in some way. You’re basically choosing to view the world in terms of ‘me versus them’ as opposed to ‘all of us.'”

My face flushed. I’d always thought of sympathy and pity as “noble.” I’d never considered their negative aspects.

I felt like she was shaming me.

I never forgot our brief exchange. It’s popped into my head again and again, all over the world — in New Delhi, Varanasi, Bucharest, Istanbul, Sofia, Sarajevo, Marrakech, Minneapolis — every time I’ve felt compassion well up within me.

Like that time I saw a girl standing beside a cow in Udaipur, India (see picture up top). Why was she so dirty? And where were her parents? And why wasn’t she in school in the middle of the day? I felt sypathy and pity for her.

It’s made me ask, If these emotions creates separation, then what emotion creates unification?

Two weeks ago, Ron helped me identify this other, less “noble” emotion.

I met Ron for the first time at his studio apartment in Minneapolis’ Elliot Park neighborhood. I’d come there to interview him for an article I was writing about the link between health and homelessness.

The literature I’ve read suggests that poor health and homelessness create a vicious cycle, with each factor making the other worse or more likely to happen. That is, poor health can lead to or worsen homelessness. And homelessness can lead to or worsen poor health.

In 2013, Ron was diagnosed with latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA), or diabetes type 1.5. It’s a subset of diabetes that progresses slower than diabetes type 1; most people don’t develop LADA until they’re in their thirties or older.

Ron’s done construction and janitorial-type work for most of his life.

Whereas I sit on my ass in an office most days, my muscles atrophying, Ron’s jobs require a fair amount of physical exertion. Which is tough when you’re a diabetic. A couple of months after his diagnosis, Ron’s boss saw him trembling as he came down a ladder. He was deemed a potential liability, and he lost the job he’d held for nine and a half years.

While he’s been able to find other work, it’s been a challenge to gain rapport with employers because he’s too ill to commit to eight- to ten-hour workdays as before, and he usually doesn’t know until the morning if he’ll feel well enough to come into work that day. As he’s discovered, “Who is going to hire me when I have to take time off?”

Ron’s been hospitalized numerous times, and at one point he was in a diabetic coma. After he depleted his unemployment benefits and his savings, he became homeless. He was homeless from September 15, 2013 until May 6, 2014, when the county placed him in the interim housing unit I visited him at.

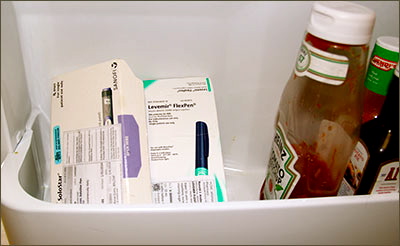

For the first time in eight months, Ron can prepare home-cooked meals and refrigerate his insulin. He hasn’t been hospitalized since he was housed. (Perhaps the literature is right; perhaps a studio apartment is a good return on investment, considering that an inpatient hospital admission costs tens of thousands of dollars.)

Ron’s insulin, refrigerated

I found Ron endlessly fascinating during the 90 minutes I spent at his studio apartment. He told me about his dead father, who was a sergeant major in the Army. He told me about his current job — upgrading a facility that’s being turned into a restaurant. He told me about his extreme fear of needles and the time his blood sugar oscillated between 36 and 586 mg/dl in a single day. He told me how he wakes up blind some mornings (a symptom of low blood sugar) and when he patted his red flannel shirt (the shirt he often wears to work) a plume of dust rose into the air. Ron fed me one compelling vignette after another, and I regretted having to leave for a meeting.

I haven’t been able to stop thinking about Ron since I met him, and when I try to articulate why, I realize it’s because Ron — and Ron’s life — made me “curious,” a word my dictionary defines as “eager to know or learn about.”

Curiosity, I read, is an emotion. An emotion that’s observed in humans from infancy to adulthood, an emotion that’s also observed in apes, cats, rodents, and other animals.

The more I ponder curiosity, the more I understand that maybe we don’t need sympathy and pity to change the world, to be humanitarians, to engage in public service. Perhaps all we need is curiosity.

Enough curiosity to interact with the kinds of people we normally never talk to, associate with, live beside. Enough curiosity to eat dinner with these people, to invite them into our homes, to listen to their needs and dreams and stories.

It seems so easy to be curious, and yet so many of us (myself included) feel apathetic.

Tonight, I googled “how do I develop curiosity?” An article suggested six ways:

- Keep an open mind

- Don’t take things for granted

- Ask questions relentlessly

- Don’t label something (e.g., as boring)

- See learning as fun

- Read diverse types of books

I was especially fascinated by the idea that “labeling” something could stifle curiosity. Just as sympathy and pity imply a labeling of oneself (or one’s circumstances) as superior to another person (or another person’s circumstances), curiosity implies a reaching out — with an open mind, with no preconceived notions — and trying to find connection.

Last night, as I pondered sympathy and pity versus curiosity, there was a moment of synchronicity. I opened the The Sun — an issue that had just arrived at my apartment — and, on the last page, I read this quote by G.K. Chesterton:

“How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it; if you could really look at other men with common curiosity and pleasure… You would begin to be interested in them… You would break out of this tiny and tawdry theater in which your own little plot is always being played, and you would find yourself under a freer sky, in a street full of splendid strangers.”

It seems sacrilegious to visit someone’s apartment, to engage in something as intimate as an interview, and then to leave and write their story and never speak to them again.

Since we met, I’ve been compelled to phone Ron, to drop by his apartment, to see what he’s up to, to see what he needs, to see if he’s feeling better. And I realize that these desires stem not so much from any sympathy and pity I feel toward Ron as from another, less “noble” emotion. Curiosity.

Sometimes I wonder if there’s any logic to this world, if people cross our paths for a reason, to teach us what we need to learn. I’ll never know the answer for certain, but I want to say, Thank you, Ron. Thank you for making me rethink the world.

Read the article I wrote about Ron here.

4 Responses to “A Guy Who Made Me Rethink Sympathy and Pity”

Jim Molnar

Compassion, as I understand it, is less like the dictionary definition you cite, than the curiosity you refer to from the article and Chesterton’s quotation. It’s certainly not pity and more empathy than sympathy. Etymologically it means “to suffer with” and suggests more of an identification with others than separation, which clearly pity encourages. Equating it with pity is one of those mistakes that comes from depending on a thesaurus without digging deeper (or on an unfortunately shallow dictionary).

Compassion is one of the root values of Zen philosophy, for example, which teaches that a (or the) main purpose of sitting meditation is realizing oneness with all beings. Where pity is an emotion that rises to some degree from judgment, compassion rejects judgment and embraces awareness and understanding, which involves curiosity that inevitably leads to engagement.

Words are important, but not as important as experience. Your experience with Ron was a compassionate one — one that went deeper than pity and even curiosity. Your heart and your writing show that so very clearly.

lmimsdahl@gmail.com

Jim, thanks for schooling me on the etymology of compassion. I’ll update this blog post to read “made me rethink pity and sympathy.” Or, at very least to point out that some people (myself included at times) have labeled our feelings as “compassion” when what we were truly feeling toward a person or a person’s circumstances was “pity” and “sympathy” (or other feelings that lead to separation as opposed to the oneness that Zen philosophy teaches).

I agree with you that the experience I had with Ron transcended mere curiosity although curiosity was a big part of it.

I’ve witnessed an evolution in my life over the past year — I feel more curiosity (or perhaps I’ve been engaging in a more extroverted thought process). Either way, I’m more interested in writing about other people and it seems to be positive development (from a public service perspective).

Jim Molnar

Lori,

Your focus on place-based writing as an avenue to understanding — and action — reinforces my admiration for you as a writer and person. Unfortunately, too many Americans have little inclination to venture into the wider world , and if they do, self-indulgence plays a big part in it. For many tourists, their judgments rely heavily on comparing the lives, cultures, and individuals they encounter with what they perceive and how they live at home.

Again, your experience with Ron accepts him on his own terms in his own environment. You learned not only about him, but from him. You learned about yourself as much as about him. Curiosity, to be valuable, must embrace both.

Your essay also emphasizes how we should approach what’s close to “home” with the same openness and, yes, compassion, that we bring to bear when we seek meaning and understanding farther afield. Traveling is a way of seeing, in a sense, a way of being. It doesn’t necessarily require that we go beyond our own backyards, our own neighborhoods, our own communities, which offer as much opportunity to learn and grow as sitting in a Paris café for an afternoon or spending a year in a Bangladesh garment factory. Not to mention months in an forward base in Afghanistan.

I admire your work and your perspective. If all traveling is, in a way, a search for home, we’ve not reached our destination until we accept all the world as home.

lmimsdahl@gmail.com

Thanks, Jim. I’ll always consider your writing class one of my pivotal places. It was the place where I first understood the difference between vacation and travel and the place where I realized that travel isn’t so much a destination as a way of seeing the world. I’ve found it fascinating to travel within my hometown; thanks for planting the seed in my head.