Ron’s symptoms began in November 2012: dizziness, impaired vision, lethargy, weight loss, and thirst. The 55-year-old had the sense that something was wrong. But he didn’t go to the doctor right away. Ron’s familiar with pain. He’s done construction and janitorial-type work most of his life and it’s entailed plenty of physical discomfort. Maybe that’s why he toughed it out initially. But after three months, he made an appointment at Hennepin County Medical Center’s Brooklyn Center Clinic.

The day of that appointment — February 25, 2013 — is now seared in his mind. That Monday, Ron recounted his symptoms to a physician and she ordered lab work. Before he left, technicians took samples of Ron’s blood and urine.

That night, at 8:56 p.m., Ron was home, preparing for bed, when he received a phone call from his doctor. She told him his lab results were abnormal. His blood sugar levels were off the charts. She told him he needed to go to the emergency room immediately; if he went to sleep he might not wake up. Ron describes it this way: “God was in the Brooklyn Center Clinic at nine o’clock that night.”

The diagnosis

Ron was diagnosed with latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA), also known as slow onset type 1 diabetes and diabetes type 1.5. LADA is a subset of diabetes that progresses slower than type 1; many patients don’t develop it until they’re in their thirties or older.

Since his diagnosis, Ron carries this backpack with him everywhere. The backpack contains gummy bears and other food that he can eat if his blood sugar levels suddenly plunge.

Though there’s a diagnosis, Ron’s case continues to dumbfound physicians. For instance, despite his disease, many of his health metrics — like weight, cholesterol, and blood pressure — remain stellar. And, although diabetics experience blood sugar fluctuations, Ron’s are particularly extreme. For instance, on June 1, 2013, his blood sugar oscillated between 36 and 586 mg/dl in a day. To put that in perspective, The American Diabetes Association recommends that a person’s blood sugar levels be between 70 to 130 mg/dl when fasting and less than 180 mg/dl after eating a meal.

Life as a diabetic

Because he has an “extreme” fear of needles, Ron says that pricking his skin to test his blood sugar level is particularly difficult. He dreads the mornings because “the first thing I have to do [when I wake up] is be uncomfortable.”

But that’s not the half of it.

Shortly after being diagnosed last year, Ron lost the job he’d held for nine and a half years. His boss saw him trembling as he came down a ladder and deemed it too dangerous for him to continue working. (Although Ron has been able to find other jobs, it’s been a challenge to gain rapport with employers because he can’t always commit to eight- to ten-hour workdays as before, and he usually doesn’t know until the morning if he’ll feel well enough to come into work. As he’s discovered, “Who is going to hire me when I have to take time off?”) After his diagnosis, Ron’s condition worsened and in the summer of 2013, he experienced a diabetic coma. His unemployment benefits ran out. And on September 15, 2013, he became homeless.

Homelessness and Hennepin Health

While he was homeless, Ron lived with friends and at the Salvation Army. Kim Evers — a certified diabetes educator at Hennepin County Medical Center’s Whittier Clinic — has worked with Ron. While he was homeless, Evers witnessed Ron’s health deteriorating and she attributes his homelessness to some of that deterioration.

More broadly, Evers believes that poor health and homelessness is a “vicious cycle.” That is, Ron’s homelessness contributed to his poor health and his poor health contributed to his homelessness. Why is homelessness so challenging for people with medical concerns? Evers weighs in, from a diabetic standpoint:

- Nutrition is paramount for a diabetic, but the food that is most accessible in shelters and on the streets is often highly processed and sugar-laden, devoid of nutrition.

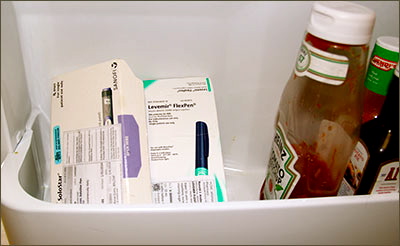

- Insulin needs to be kept cold to prevent spoiling, but homeless people may not have access to a refrigerator.

- It’s important for diabetics to maintain a regular meal schedule, but this may be difficult to do when a person is transient.

- Diabetics may get tired easily and need to rest, but some shelters require people to vacate during the day and it may be unsafe or unfeasible to sleep on the streets.

- Homeless life is stressful. Stress hormones cause blood sugar levels to rise.

Many health care experts and organizations are now acknowledging the link between health and homelessness, Hennepin Health among them. In 2012, Hennepin Health used some of its reinvestment initiative funds to rent out transitional housing units in an apartment complex that is owned by the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority.

The contract specifies that Hennepin Health will prioritize members who are homeless — and either in inpatient care or recently discharged from inpatient care — with high risk for hospital readmission due to lack of housing and social supports.

In April, Evers contacted Neri Diaz, MSW, LGSW, Whittier Clinic senior social worker. Evers remembers telling Diaz, “Ron just can’t be homeless any more. This is dangerous. We have got to do more for him.” Diaz contacted Hennepin Health’s social services navigation team, asking that Ron be considered for a vacant unit in Elliot Twins. Evers wrote a letter to Hennepin Health to document the medical necessity of the housing support.

Ron’s studio apartment at Elliot Twins

Since moving in

While he was homeless, Ron reveals that his diet — like the diets of so many people who experience homelessness — consisted almost entirely of inexpensive, highly processed food that was bought at convenience stores and fast-food restaurants or served at the shelter. As a result, the meal he prepared on May 6 — in the kitchen of his studio apartment — was the first “home cooked meal” he’d eaten since September 15, the day he became homeless. Ron’s insulin is now refrigerated and he has been able to rest when he needs to.

Since he has been housed, Ron has not been hospitalized.

Ron’s kitchen at Elliot Twins

Ron’s insulin, refrigerated

But hurdles remain. Ron explains that he wakes up blind some days (a symptom of low blood sugar). He has stage two kidney failure. He’s got neuropathy in his right foot. And despite consulting with many doctors and taking the medications prescribed him, he continues to experience extreme blood sugar fluctuations. Ron says that the housing Hennepin Health has provided him is “wonderful,” but acknowledges that the road ahead is still a challenge.

Hennepin Health believes that housing is an important part of keeping members healthy and is currently trying to secure long-term supportive housing for Ron.

Do you know a Hennepin Health patient who might meet the criteria to participate in the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority/Hennepin Health interim housing project? If so, please contact Kim Nguyen, Hennepin Health social services supervisor, at Kim.Nguyen@hennepin.us

Article appeared in the June 2014 Hennepin Health newsletter and is available here.